In the fall of 1981 in San Pedro, California, I led a double life. By day, I was the senior class co-president, well liked and respected by my peers and teachers, if not Homecoming court-popular. As a student, I was something of an underachiever — I ended up getting into both Berkeley and Oberlin, but I was often bored in class and put in the minimum effort required. I read Sylvia Plath and Kerouac and felt that nobody knew “the real me.” Perhaps all teenagers feel this way. But in 1981 in L.A., there was a home for a certain kind of young person who felt a dissatisfaction, a longing for something unnamed, and this “home” was the punk rock scene.

So by night, I was a punk rocker. My female friends and I would don thrift store dresses, ripped tights and combat boots while our male counterparts wore ripped jeans and band t-shirts. We would drive to various nightclubs or halls or occasionally garages to hear bands like The Minutemen, The Dead Kennedys, Sonic Youth, and, once, at the Whisky a Go-Go, X. At these various venues, I would listen to music that was so loud my eardrums often rang for days, flirt with pale, emaciated boys with cropped hair and multiple earrings and (mostly) eschew the beers and clove cigarettes passed around as I had a very un-punk preoccupation with conserving brain cells and avoiding lung cancer. Just as I felt I didn’t quite fit into high school world, I also didn’t totally fit into punk world. More than once I chewed out boys wearing T-shirts bearing Sharpie-drawn swastikas.

But it was exactly because I half-lived in both of these worlds that I was able to pull off the most exciting thing that ever happened in the history of my school: getting Black Flag to play on the outdoor steps of the front entrance during lunch.

I made arrangements with our very cool student council teacher, Jake, and got permission to have “a surprise band” perform at lunch.

Black Flag was the heavy-hitter of the South Bay punk rock scene, a hardcore band with legions of fans, a few record albums, a history of altercations with the L.A. police and the closest thing the punk scene had to a celebrity, lead singer Henry Rollins.

I don’t remember the details of the arrangements. I know that one school night I talked to Chuck Dukowski, Black Flag’s bass player, on the phone for nearly two hours. (How had I gotten his number? Through a friend? Or had I simply looked him up in the phone book?) He was very nice, asking me about teachers and classes, and he told me that, having once been a student there, it had been his dream to come back and play at Pedro High. I made arrangements with our very cool student council teacher, Jake, and got permission to have “a surprise band” perform at lunch. My friends knew but were sworn to secrecy — if word got out that Black Flag was playing at San Pedro High School, every punk girl and boy in L.A. would ditch school, crash our lunch concert and almost certainly cause a riot.

I went to school that day with intense excitement, and at lunchtime, I didn’t bother eating but simply hurried to the steps to make sure everything was ready. Three thousand students? Check. Administrators looking askance at these punk twenty-something men setting up their equipment? Check. Jocks laughing and calling the band members “faggots” (the catchall derogatory term used by pre-lingual teen boys to name anyone who is different from them and therefore unfathomable)? Unfortunately, check.

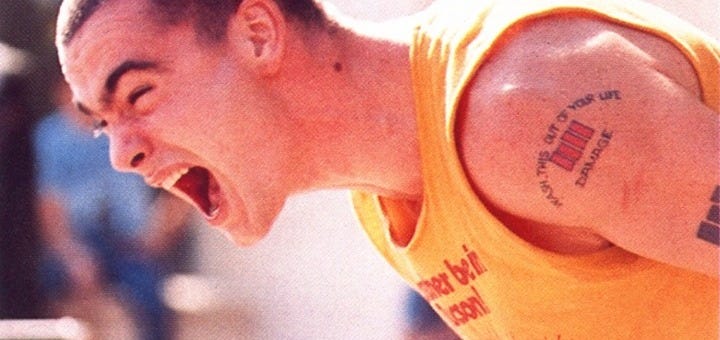

And then Black Flag began to play. The drums and guitar were heart-poundingly loud, and Henry Rollins, with his nearly-shaved head, t-shirt with sleeves ripped to reveal the Black Flag symbol (four black rectangles, like discordant piano keys, with the band’s name) tattooed onto his upper arm, began to sing. Or maybe not sing so much as scream the lyrics into the microphone. Lyrics that went something like:

I got a six pack and nothing to do

I got a six pack and I don’t need you

$35 and a six pack to my name

SIX PACK!

Spent the rest on beer so who’s to blame

SIX PACK!

They say I’m fucked up all the time

SIX PACK!

What they do is a waste of time

SIX PACK!

The administrators unplugged the microphone. That did not slow down Henry Rollins, who simply screamed even louder, veins pulsing on his forehead and neck, mouth wide open, looking to my 17-year-old eyes like the sexiest god of creation and destruction there ever was. But the jocks took a more critical view of the situation and began throwing their lunches at the band — sandwiches, apples, bags of chips, whatever was handy. Other students booed. The band kept playing, Henry screaming louder. I don’t remember now if they ever finished their set.

But I do remember, later that afternoon, Jake telling me that the principal was “very disappointed” in me. I was a student who sat in the front row and raised her hand and wanted adults to like her; the idea that the principal was “very disappointed” in me was worse to me than detention.

But I got over the news pretty quickly. People I barely knew told me for weeks afterwards how “excellent” that concert was. At nearby local gigs, punk kids whispered to each other as I walked by. And when my first novel was published, years later, I got a letter from a fellow Pedro grad, two years my junior, who told me that she’d always looked up to me for being “the coolest girl in the school.”

Does anyone ever feel like she is the coolest girl in the school? I know I never did.

But now, at fifty-one years old, I can confidently make this claim to fame: For a few weeks back in the fall of 1981, thanks to Black Flag, I was the coolest girl in the school.