My Father’s Final Chapter Wasn’t What He Planned—and Created a Family Rift That Won’t Heal

How can I find peace with it?

My father died around midnight on September 9, 2021, and since that day, the hardest part of mourning his life has been accepting that he didn’t get the death he wanted.

In June of that year, I received a worrying call from Connie, my father’s wife. She told me that my 91-year-old father had lost his ability to walk and could no longer be cared for at home. By the tone of her voice, I knew at that moment that she wanted to place him in a facility. Likewise, I knew that her intention to do so would cause a rift in our relationship.

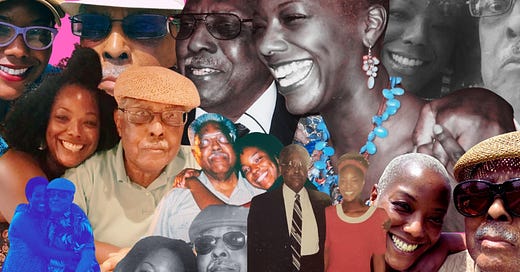

Here was my father, Curtis L. Wrenn, Sr., a Black man born in 1930 to a midwife and a sharecropper. My father spent his life fiercely preserving his autonomy. As a teenager, he was raised in segregated Birmingham, Alabama where his first jobs away from a farm and cotton field were working at a shaved-ice stand and slinging peanuts at baseball games. He was a retired Army veteran who served three combat tours in Vietnam, fathered seven biological children (of which I am the youngest), and married three times. He earned a master’s degree in hospital administration and ran hospitals in Maryland and Minnesota. More than anything, he was a thinker. An armchair philosopher. A preacher. When I was a child, he told me, “Though there are many prophets, there is but one God.” According to my father, every prophet—be it Bahá'u'lláh, Buddha, Jesus, or Mohammad—is sent by God to plant a divine message in an appointed place, people, or period.

Beyond his self-acquired expertise in the realms of theology and philosophy, or maybe because of it, my father also fought his own legal battles. As a pro se litigant (meaning he represented himself in court), he brought numerous lawsuits in district and federal court for employment discrimination. At least one of his legal filings was heard by the Supreme Court when Justice Thurgood Marshall was on the bench.

Who would ever think that not leaving this world on his terms could be an option for a man like this?

I knew my father wanted to die at home; hell, we all knew. So, when I got Connie’s call, as far as I was concerned, it was time to deploy and defend. That same night, I put gas in my car and began the seven-hour journey to their home in Elizabeth City, North Carolina. While I drove, I felt a pit in my stomach as I prepared to confront the situation. I was praying for strength and asking God for wisdom to appeal to Connie’s sense of fairness, praying for wisdom. I was determined to be a steward of my father’s wishes.

Upon my arrival, I met with my stepmother and brother to discuss next steps. They agreed to my request for a three-day grace period to arrange home care. Nevertheless, within 48 hours, my stepmother scheduled a sales tour at a local assisted living facility, which was noticeably lacking the round-the-clock care Daddy required.

The following week, my father was admitted as a full-time resident, a placement I deemed inappropriate for his needs. I expressed my fear that he might fall without proper care. Sadly, my concerns materialized in July when he suffered a concussion and skull fracture, leading to hospitalization. The ongoing struggle between managing expectations and accepting his new reality weighed heavily on me.

The situation added layers of resentment to an already emotionally charged end-of-life scenario —and a complex stepparent-stepchild relationship.

After a stint in rehab, my father gained strength and mobility. By September, he returned to living with Connie, but he would never again see the inside of the home they shared for more than 20 years. Instead, she moved them both to a continuing care residence in a different state. As his health rapidly declined, the stark contrast between the caregiving ambitions of his wife and me, and the difficult realities of decline, became painfully evident.

In navigating the intricate eldercare system, Connie and I found ourselves at odds as our dual approaches clashed. While I was determined to uphold his wish to die at home, she sought immediate relief through professional care due to the understandable exasperation and fatigue of being his primary caregiver for decades. After her years of daily sacrifice, my advocacy may have seemed controlling and presumptuous to her.

The situation added layers of resentment to an already emotionally charged end-of-life scenario —and a complex stepparent-stepchild relationship.

Due to Connie’s actions, which included her telling me to leave my father's home and even exhibiting physical aggression the day she raised her hand to slap me, I felt betrayed. It seemed as if the nearly 40 years she'd spent married to my father, bestowing countless gifts for my birthdays and holidays, meant little in those moments. These events have left indelible marks on my memory, influencing the way I perceive our shared history.

About two weeks after entering that new residence, my father passed away, or “transferred” as he would have called it, with Connie lovingly by his side.

In the aftermath, a profound silence settled between Connie and me. The wounds of that time still persist in the brokenness of our relationship. I haven’t spoken to her since that night, more than two years ago, when she called to tell me that Daddy died. Without her, I miss the companionship of someone who loves him as I do.

Even so, his presence remains everywhere: his writings, his voice on old cassette tapes. When I see his belongings stashed throughout my house, I hear myself yelling, “Hi, Daddy!” in my head (and sometimes aloud). Then, my mind hears his delight, the enthusiasm in his orator’s voice when he would say, “There’s my girl!” or “Go get ‘em, Penny D!” His bear hugs left me breathless. Oh, how I miss his face lighting up when I enter a room!

I cannot change how his final chapter unfolded, but I take comfort in his own words, written years before for one of his graduate studies, and so relevant to this journey: We always live at the time we live and not at some other time. Which is to say, I suppose, all we can do is our best —our right-now, present-self, not-nearly-as-good-as-we-hoped best.

My father and I had much more to learn from each other, but I know his spirit lives on through me. Continuing to grow in wisdom, leading with empathy, and standing up to injustice, as he advised, I honor his legacy. I have faith that if I keep on keeping on (another one of his mantras), we will meet again in the “eternal reality,” as he called it. We will sit side-by-side, elevating our legs in matching brown leather lay-z-boy chairs and watching old Westerns on a big-screen TV, picking up where we left off in the forever friendship and forever union we started here.

We're honored to have Penny share her incredible story - she was unable to join us at TueNight's Birthday Bash, thank you for sharing it with us via YouTube.

ICYMI: Watch TueNight’s Birthday Bash in full, here — we’re also sharing a few of our fave photos taken at our event, here.