Editor's Note: We're proud to have AARP as a sponsor because, like us, they take a bold approach to changing how we think about aging by challenging outdated beliefs and exploring new ways to spark conversation and empower people to choose how they live as they age. Join us as we explore how to #DisruptAging together.

I lived the first 53 years of my life fully invested in the narrative that I was my mother’s firstborn child, her firstborn daughter. I had been raised on the bittersweet love story of my parents.

I come from a family of storytellers, and there is lore that lives inside my family about how my parents met at a dance at the armory. He was there with his soon-to-be ex-girlfriend, and she was there with her cousin, who apparently encouraged her to talk to that handsome Willie George McConner. The love story that followed was epic. My aunts would talk about how quickly they fell in love and married, and how badly they wanted babies together. In the story that had been repeated so many times throughout my childhood, it was my father, William George McConner, the eldest son of Annie and Jacob McConner’s brood of six children, who saw my mother as his soft place to land, his redemption song.

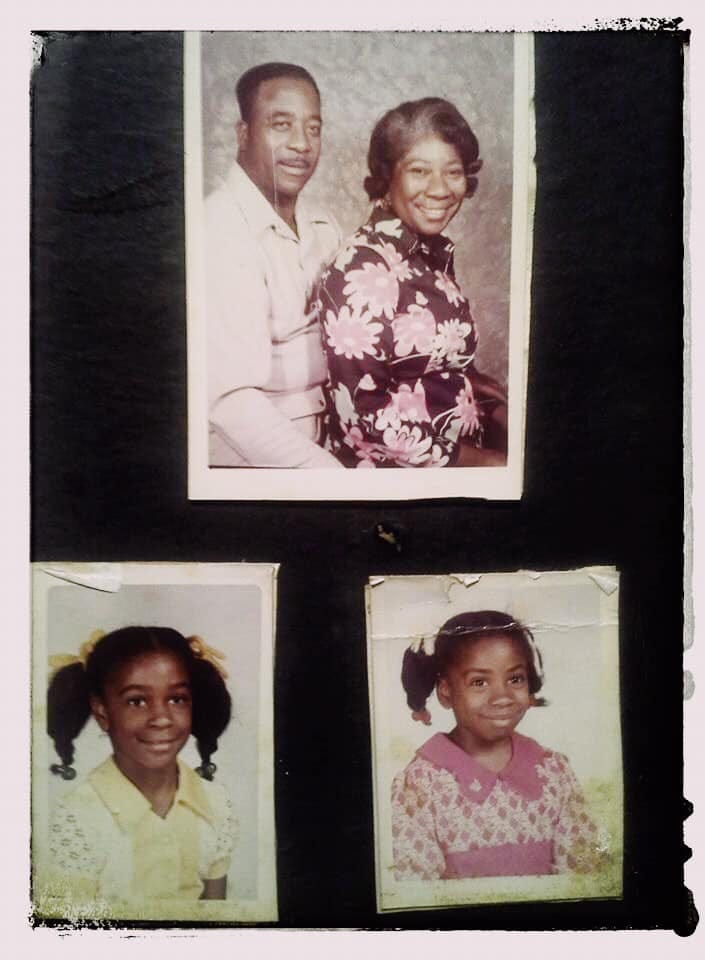

Thirteen years my mother’s senior, my father was born and raised in eastern North Carolina, in the same community where my mother was raised and where we can trace our family back seven generations. Short in stature, big in personality and presence, my father was a looker with pecan-brown skin. He had a legendary temper and a reputation for being a straight shooter and a ladies’ man. As soon as he was old enough to leave school, he did just that. He got a job as a brick mason and made enough money to buy a one-way ticket to Brooklyn, leaving North Carolina behind. There he would marry and father two girls, Mary Anne and Michelle, my older sisters.

My mother, on the other hand, was the middle child of Irma and John Kinsey. Her childhood was marked by poverty and unexpected death: first, with the passing of her older brother Owen, just a toddler, from pneumonia, and then her father, who worked tirelessly as a tenant farmer, from a burst appendix. He was in his thirties. This left my grandmother, who had contracted polio as a child and moved in the world labeled as “lame,” to figure out how to care for my mom, just four years old, and her baby brother, my Uncle Coley. They were often separated from one another as they moved around the small, rural communities of eastern North Carolina, between kith and kin, for two years during the Great Depression. Eventually, my mother would be taken in by my grandmother’s sister, our Great Aunt Betty, a teacher, and her husband. They would raise her until she left home in 1950 to attend Bennett College for Women in Greensboro, North Carolina.

Mommy was taller than average, with warm, dark brown skin, rail-thin and full-chested, with an overbite inherited by all her progeny,—and wore glasses. My Uncle Coley relentlessly teased her when they saw each other, calling her “big nose and snake toes.” She never felt pretty, but she was smart, a great orator, and she knew what she wanted to do with her life: She wanted to be a registered nurse. At Bennett College, one of two HBCUs in the country for Black women, she could make that happen.

Twelve years after becoming a nurse, Mary Ella was there that night at the armory, where she and Willie George first started their dance together. In the four years that my parents were married, they experienced two pregnancy losses, my birth, my father’s cancer diagnosis, and the birth of my younger sister, Georgette, three months after our father passed away. Seven years after her first marriage, she married our stepfather, Charlie, in the living room of his house in Washington, D.C. My mom and stepdad were old high school friends, him with two teenage boys, and her, a young widow with two girls. Charlie would become our daddy, legally adopting us, and Fred and Charlie, Jr., our big brothers.

To me, my large Black southern blended family, and the friends who knew her, mommy was pretty damn amazing. When I was a kid, I was hella active. Always running, jumping, playing… whatever. My sister and I took tap, ballet, and jazz dance classes. Saturday mornings were for high buns and top-knot afro puffs. There were multi-hued little Black girls in pink leotards, shiny black tap shoes, and black or pink ballet shoes. We danced to Chaka Khan, Louis Armstrong, and The Wiz. I loved all this movement, and you would think being this active would help me be more graceful, but it didn’t. I was clumsy as hell. If it was possible to get poked in the eye, I did. If there was a way for me to sprain a finger, knock a permanent tooth loose or break my foot, I found that way—over and over and over again. My mother, the nurse, used to say, “Billie, if you live to be 16, you will live forever!” That encouraged me to watch my steps, slow down and be careful. Lord knows, I have tried, and I also know I won’t live forever.

I have lived 20,075 days. My mother lived 24,820.

People who follow me on social media know how much I love my mom. They also probably know that hers was the first death I would bear witness to, when I was 31. This was a role I took very seriously as her dutiful, firstborn daughter.

It’s the little things you always seem to remember. Her laugh that came from deep inside her belly, or her perfume. White Shoulders or Charlie perfumes were always present in our home; Jean Naté was a close third. The way she would hum a random tune while scratching my scalp or cooking something so simple as a pot of pinto beans. That hum and the power in her dark brown fingers created magic that seemed to linger. I miss her laugh, that hum. I miss her.

In the first winter of the pandemic, a family relative I didn’t know reached out to us on social media:

“I found you on Ancestry.com. I think your mother was married to my grandfather.”

Me: “Is your grandfather’s name William, or Charlie?”

“No. Roscoe.”

Wait. Who the hell is Roscoe!?!

Unbidden, this new piece of my mother’s life story had made its way to me, through my newly found eldest nephew Terrance — her eldest grandchild. He came to tell us the story of how my mother had been in an abusive marriage in her early 20s. Roscoe was her first husband; that marriage had taken place 12 years before she connected with our father and began walking a new path where she felt safe and loved. Before all that, my mother was married to a man who mentally and physically tormented and isolated her.

My heart began to race and my face got hot as I listened to my nephew tell my mother’s story. I thought I knew all her stories. I had committed them to memory almost like an act of fealty to her legacy, which I have shared with my own children. To learn of her first marriage, and the deep loss she experienced as a result of that relationship, flooded my body with sadness and anger, and my mind with questions that will never be fully answered.

She had met him during her post-grad program at L.Richardson Hospital, the “colored” hospital in Greensboro, North Carolina, which enrolled Bennet students after they completed their first two years of general studies. My mother married Roscoe two months before her 21st birthday; they moved to New Jersey after she completed her nursing program.

Her first marriage had also made her something she had not been before: a mom. It breaks my heart that she was separated from her children — my eldest brother, Michael, and my sister, Patrice — the first babies she held in her body that she would have to leave behind to save her own life. Whom she would never again see on this side of the veil. They, too, would both pass away before their story was revealed to me by little green leaves on the ancestry.com website.

Her story, their story, has opened a portal to a new journey of reunification and healing for our family and is allowing me to see my mother again in a whole different way. Her story, filtered through the years of someone else’s voice, reminds me that you don’t always see the harm or trauma a person has gone through or is walking with. It makes me angry to know my mother suffered at the hands of a violent person. But I also feel joy and so much love and gratitude for the love she could still access for my sister, me, our other siblings who would come to call her mom, and all her grandbabies. I’m also curious if she could access that same love for herself.

There is a belief that grief is carried somatically in our lungs, so it’s no surprise that it was where sarcoidosis took hold of her breath at the end of her life. But I’m so grateful that grief didn’t destroy her beautiful heart. I am also grateful to be a keeper of stories. It’s an honor to hold sacred space as people allow whole worlds to fall from their mouths into my hands. Stories wrapped in love, grief, anger, humor, and joy. Truths smoothed out, or raw and jagged, are an offering. A balm that heals. I’m sitting here with a new part of my mother’s story in my hands. It’s new to me but old at the same time, like chipped fine China in a consignment shop.

My mother was a person with a complex story of grief and trauma that has found a way to live on past her physical presence of 68 years of life on this planet, like coordinates of a supernova signature that no longer exist in this dimension. We know the story is real, and we have been left to decipher the truth of her journey on our own.

I’m proud to say I am Mary’s daughter. I’m honored to be a keeper of her story.